Queer Revolutions: Gender Nonconformity in the 18th century

Inquiry Question 1: Why might someone in the eighteenth century choose to live as a different gender than they were assigned at birth?

Inquiry Question 2: What are the advantages and disadvantages of using personal letters, biographies, and magazine articles as primary source documents?

Background Reading for Students

Historical Overview: Gender nonconformity in the past, and today

For most of history, people have “transed” gender. According to Professor Greta LaFleur, since antiquity, mentions of gender-nonconforming people appear “consistently in fiction, religious texts, church and court records, and even in texts authored by trans people themselves.” Examples of gender-nonconforming people include the Hijra in India, the Samoan Fa’afafine, and the Two-Spirit of various North American indigenous nations. Western cultures and societies have been largely limited to a strict binary of male and female concepts, partly due to the influence of ancient Greek philosophy, the role of the Catholic Church in Western global expansion, and the rise of industrial capitalism. While there are examples of people transing gender in the Western world since records were kept, it has only been in the last 60 years or so that we have had a specific word—“transgender”—to describe those experiences and, at times, identities. This evidence reveals that gender variance has deep historical roots, appearing across different cultures and time periods, suggesting that the concept of transing gender is not a modern phenomenon, but an enduring one.

Recognizing this historical continuity opens up new possibilities for understanding the past. As we encounter examples of gender nonconformity, we should ask what their experiences meant within their own time and place. Rather than dismissing these stories as anomalies or forcing them into modern categories, we should practice the skill of historical empathy. We should understand past experiences on their terms. At the same time, we should recognize the common threads of human diversity that connect us across centuries. We can use our modern frameworks of understanding to conceptualize their lived experiences.

So why did some people trans gender in the eighteenth century? It is as complicated a question back then as it is today. Many reasons had to do with times of social, political, and economic unrest. For some, wearing clothes of a different gender than what they were assigned at birth opened up new economic opportunities. Enlisting in the Army or Navy would easily pay more than jobs typically available to people assigned female at birth. It could also be for practical purposes; many people would wear the clothes that made sense for the work they were doing, like pants for farming instead of skirts. It is unfortunate, but dressing in male clothing would also allow for greater freedoms in travel as well. And, of course, some transed gender because expressing their true gender identity brought them a sense of wholeness and authenticity.

Both source sets explore people transing gender, possibly for different reasons, but definitely in distinctive ways. Deborah Sampson (Source Packet #1), a poor indentured servant, joined the Revolutionary Army as Robert Shurtliff, received a signing bonus, and earned a living when jobs for those assigned female at birth were scarce. After the war, they worked as a farmer using the name “Ephraim Sampson,” which was their brother’s name, then married a man, bore children, and resumed identifying as a female. Would we consider Sampson/Shurtliff gender nonconforming or trans? Or, was Sampson seeking opportunities only afforded to those assigned male at birth. Whatever the answer is, one question we should ask ourselves is how much we should rely on our modern language and ideas to understand people from the past. Source packet #1 explores Deborah Sampson’s notoriety through two primary sources. The first is the frontispiece to a book written about their life. The second source is a letter Paul Revere wrote on Sampson’s behalf to Congress seeking a disability pension.

Across the Atlantic, the Chevalière d'Éon (Source Packet #2) lived a remarkable double life during roughly the same period as Sampson. This French aristocrat first excelled as a male diplomat, soldier, and secret agent for 49 years before living openly as a woman for the remainder of their life. Born Charles Geneviève Louis Auguste André Timothée d'Éon de Beaumont, they excelled in France’s diplomatic corps, serving at the Russian Court and later as France’s official representative in England. D'Éon then lived openly as a woman from the 1770s until their death in 1810. After losing their pension during the French Revolution, they supported themselves through fencing exhibitions. Only upon death was it revealed they possessed male genitalia, making them one of the first known cases of someone assigned male at birth living openly as female with apparent societal acceptance. Did d’Éon trans gender? Did eighteenth and nineteenth-century Euro-American society accept this gender nonconformity? Source packet #2 includes three primary sources: an engraving of d’Éon in Boston Magazine, the first page of that same article, and a letter written by Abigail “Nabby” Adams (daughter of John Adams) to her brother, John Quincy Adams, describing the rumors surrounding d’Éon in Europe at the time.

As you examine these sources, pay particular attention to the reasons that our historical actors might have had for adopting different gender identities or presentations in the eighteenth century. Look for examples of society’s approval or disapproval and consider why that may have occurred. Identify instances of bias in your primary sources by considering the author’s purpose and motives to better understand the text. Ultimately, as students of history, we possess the ability to bridge past and present using our contemporary understanding of transing gender thoughtfully. This approach allows us to illuminate historical experiences with our modern understanding of gender while respecting the nuance and complexity of the past, creating more inclusive and complete narratives of human experience.

Author’s Note on Pronouns

When writing about historical figures whose gender expressions and identities challenge traditional Western binary categories, I have chosen to use they/them pronouns as a deliberate act of allyship and to model inclusive language. This approach acknowledges that some individuals from the eighteenth century experienced a fluidity of gender identity that defies simple categorization, navigating society in ways that suggest complex relationships with gender norms and expectations. While my graduate school training emphasized that one should never use contemporary terms and concepts to study the past, I have found that one way to make the past usable and understandable to students is to do just that very thing. While historical documents may have used specific gendered language or terms reflecting the conventions of their time, using they/them pronouns acknowledges the diversity of gender identities and expressions without making assumptions about individuals based solely on historical context or limited information. The use of inclusive pronouns also emphasizes how specific historical figures openly transgressed gender norms throughout their lifetimes, living portions of their lives presenting across different gender categories. This twenty-first century convention of using they/them pronouns represents my conscious choice to honor the complexity of these individuals' experiences. As historians, we must grapple with our language choices when representing people whose lives may not fit neatly into the gender categories available in their historical periods. Since we all study history, our discipline should go beyond academic boundaries and emphasize fostering inclusivity, beginning in the classroom.

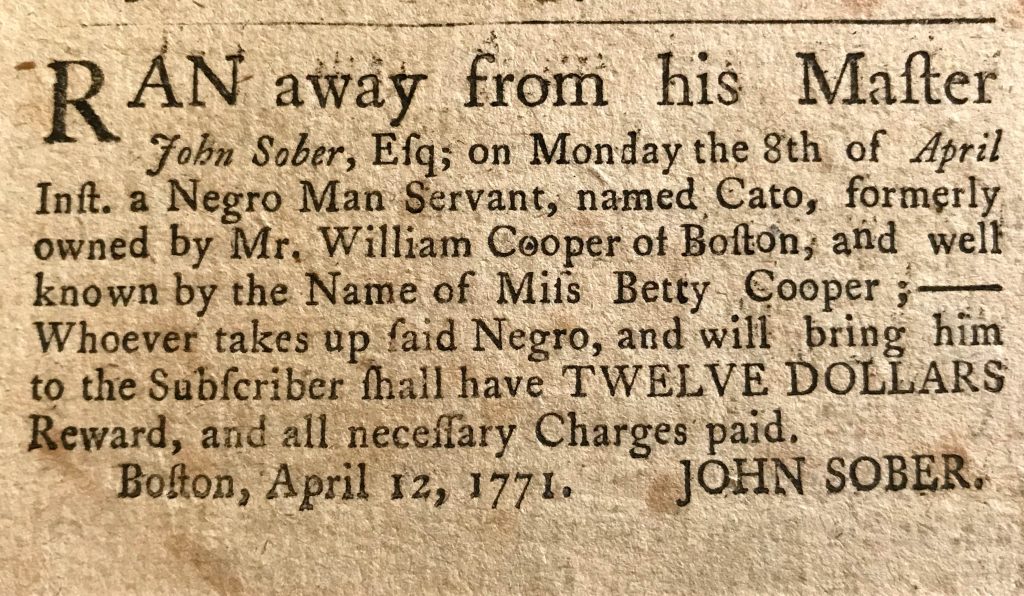

"Well known as Miss Betty Cooper," Massachusetts Gazette, 15 April 1771

Until the end of slavery in Massachusetts in 1790, Boston newspapers commonly advertised the recapture of enslaved people who had freed themselves. In this ad, enslaver John Sober seeks to find a person he describes as a Black man “named Cato… and well known by the Name of Miss Betty Cooper.” Between 1769 and 1771, Cooper's former enslaver (a Son of Liberty named William Cooper) sold her to Sober, a sugar planter who enslaved 200 people on his Barbados plantation and a smaller number in Boston. Cooper liberated herself from slavery in Boston on the 8th of April 1771. Cooper was apparently so well known to her community that her enslaver didn’t bother to include the routine descriptions usually seen in these ads (e.g., appearance, clothing).

While we can never know how Cooper identified herself or her gender, it is clear that she publicly transgressed and resisted European colonizer gender norms frequently enough as to be familiar to Bostonians. Although these few sentences about Miss Betty Cooper are written by an enslaver with the hope of recapturing her, we can use them as a window to learn more about Miss Cooper, to wonder about her life, and to inspire us to seek her and others like her in archives and memory.

RAN away from his Master John Sober, Esq; on Monday the 8th of April...a Negro Man Servant, named Cato, formerly owned by Mr. William Cooper of Boston, and well known by the Name of Miss Betty Cooper; — Whoever takes up said Negro, and will bring him to the Subscriber shall have TWELVE DOLLARS Reward, and all necessary Charges Paid. JOHN SOBER, Boston, April 12, 1771.

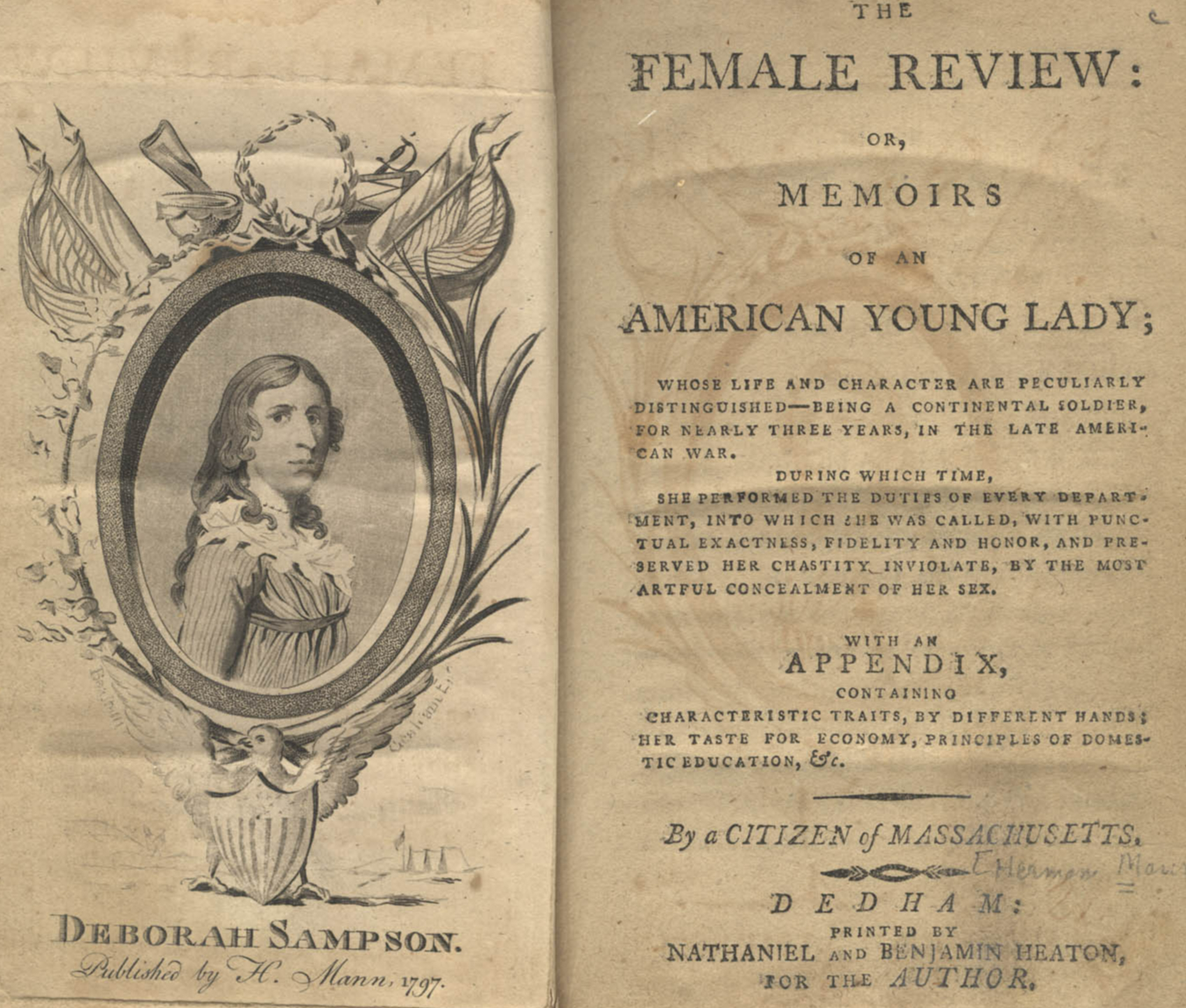

"The Female Review, or Memoirs of an American Young Lady" tells Deborah Sampson's story as a soldier named Robert Shurtliff

Displayed are the frontispiece and cover page for the book The Female Review: Or, Memoirs of an American Young Lady, written by Herman Mann in 1797. Herman Mann was a newspaper publisher primarily based in Dedham, Massachusetts. Now considered a largely fictitious biography, or, as scholar Alfred Young writes, a “tangle of fact, invention, and mystery,” the book was successful in helping Sampson Gannett secure a pension from the federal government.

The Female Review: or, Memoirs of an American Young Lady;

Whose life and character are peculiarly distinguished—being a continental soldier, for nearly three years, in the late American war.

During which time, she performed the duties of every department, into which she was called, with punctual exactness, fidelity and honor, and preserved her chastity inviolate, by the most artful concealment of her sex.

With an APPENDIX,

containing characteristic traits, by different hands; her taste for economy, principles of domestic education, etc.

By a Citizen of Massachusetts. DEDHAM: Printed by NATHANIEL and BENJAMIN HEATON, for the AUTHOR.

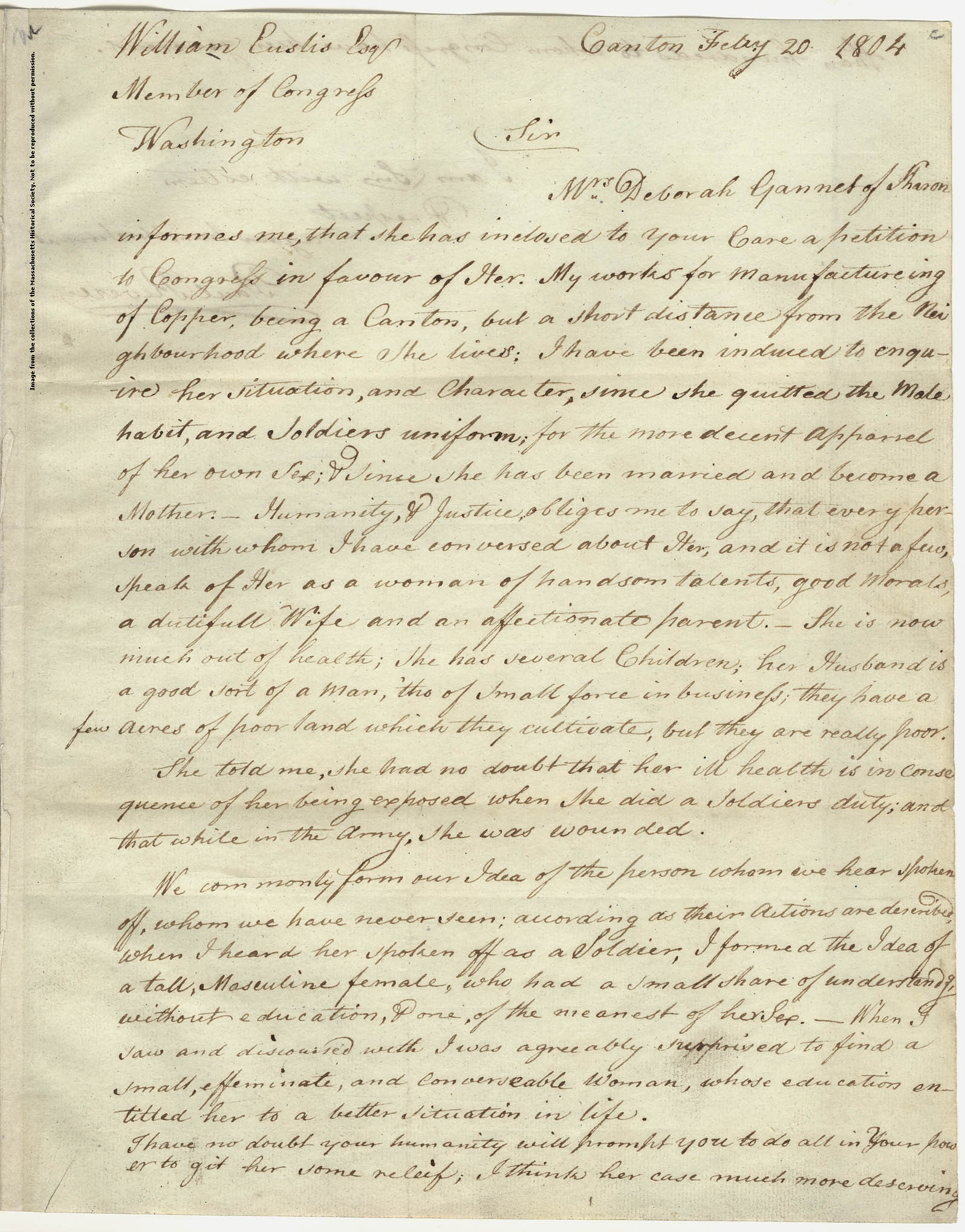

Letter from Paul Revere to William Eustis, 20 February 1804, about a pension for Deborah Sampson Gannett

A handwritten letter dated February 20, 1804, from Paul Revere to Congressman William Eustis. The letter is an appeal on behalf of Deborah [Sampson] Gannett of Sharon, MA in their attempt to receive a disability pension from the federal government for their years of service in the Continental Army. In addition to outlining the various excellent and honorable qualities of Sampson Gannett, Revere also mentions that Sampson Gannett’s declining health was due to injuries suffered during the war. Because Sampson hid most of these injuries from officials during the war, it was hard for them to provide evidence in the form of documentation. Thus, the character letter from Paul Revere and others.

I have been induced to enquire her situation, and Character, since she quitted the Male habit, and Soldiers uniform; for the more decent apparel of her own Sex; & Since she has been married and become a Mother. Humanity, & Justice obliges me to say, that every person with whom I have conversed about Her, and it is not a few, speak of Her as a woman of handsom talents, good Morals, a dutifull Wife and an affectionate parent.

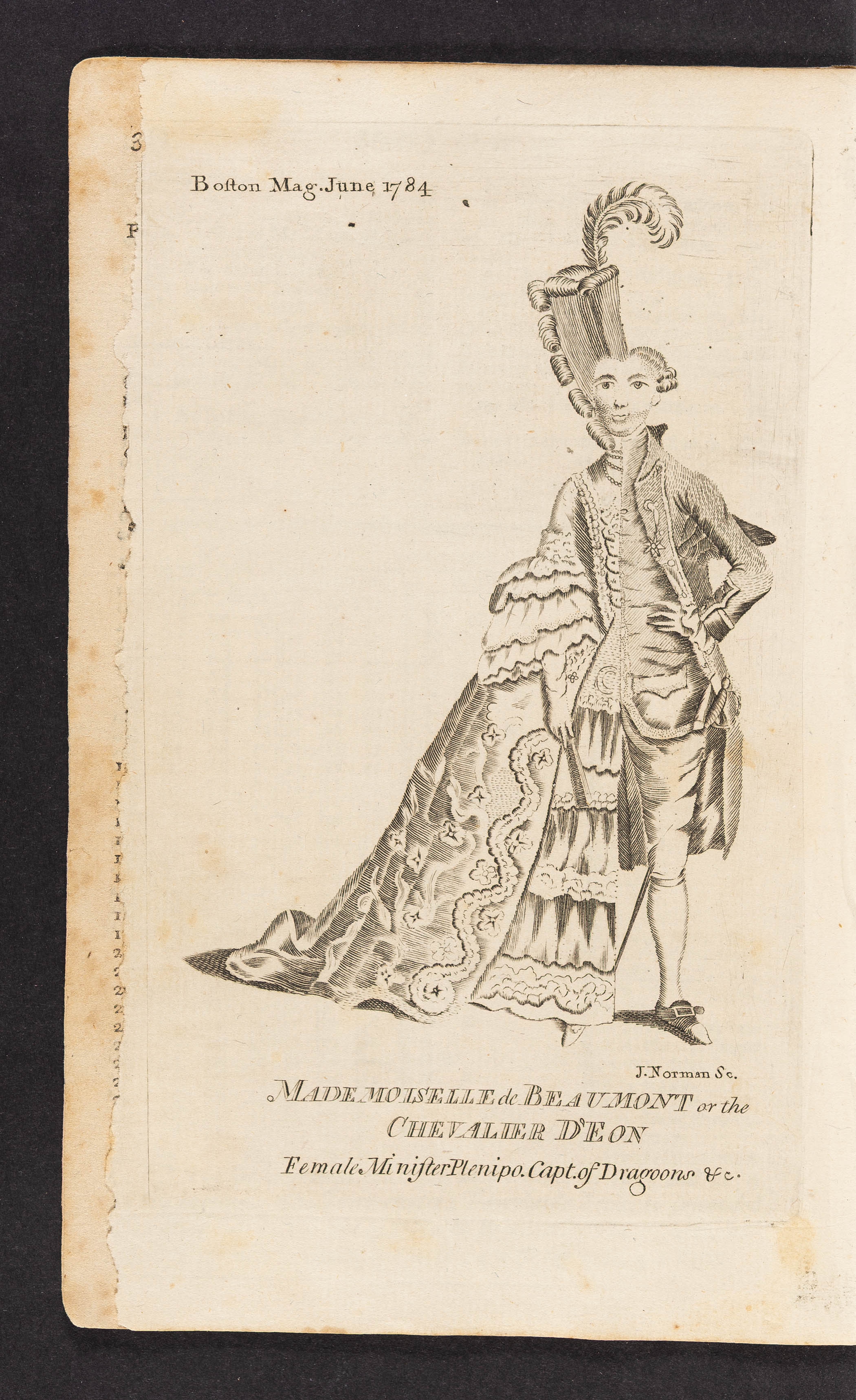

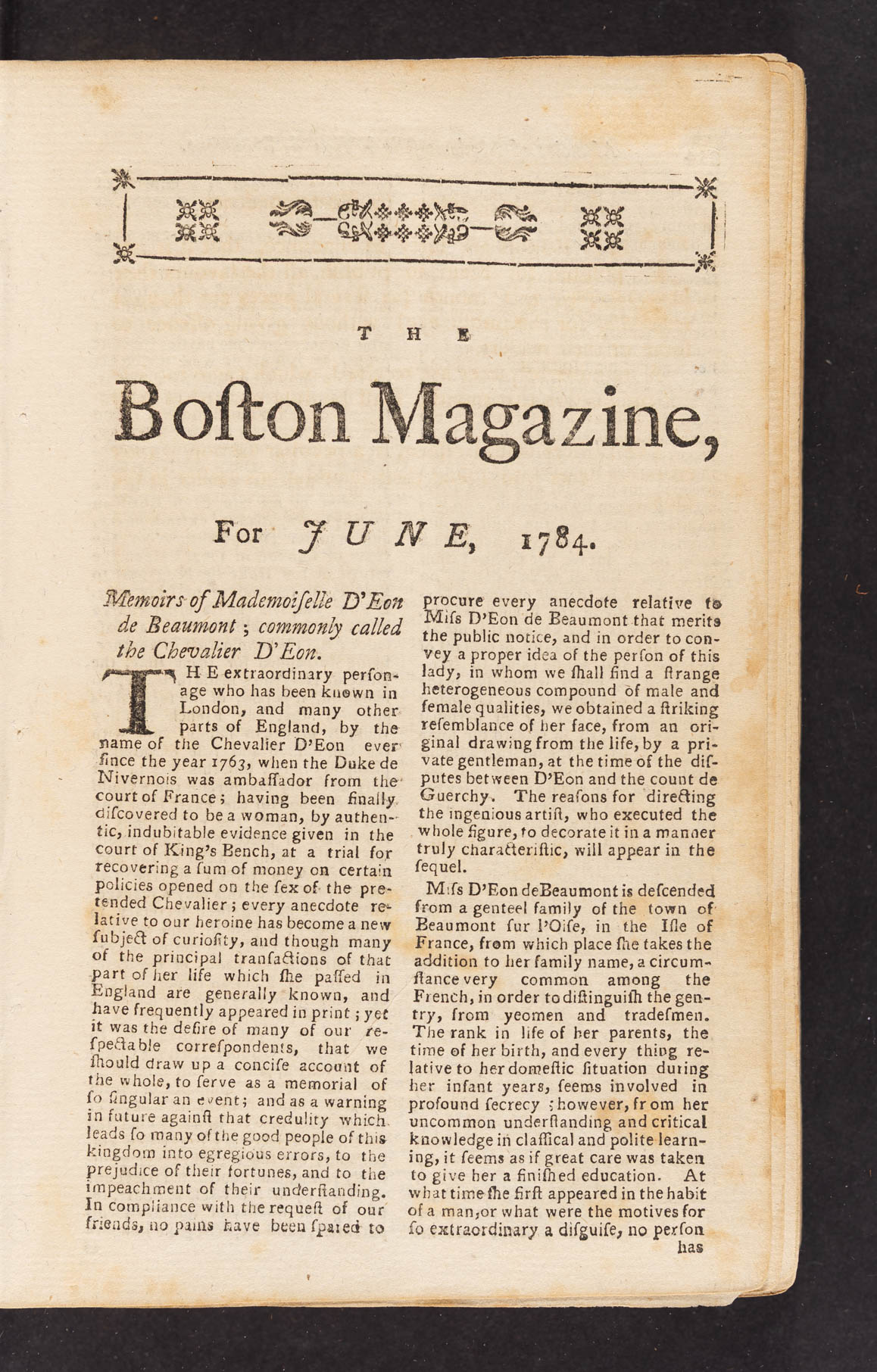

“Chevalier d’Éon,” engraving, Boston Magazine, June 1784

Pictured is the frontispiece of Boston Magazine, published June 1784. It features an engraving of “Mademoiselle de Beaumont, or the Chevalièr D’Eon.” This engraving (and accompanying article) is most likely a reprint, as a similar image is found in London Magazine in 1777. This engraving pictures d’Éon wearing both male and female clothing, mockingly challenging their identity in a manner that modern society would find problematic and unacceptable.

Assigned male at birth, the Chevalière d’Éon (1728-1810) was a French aristocrat who excelled as a diplomat, soldier, and secret agent and, from the age of 49, openly lived their life as a woman. The Chevalière was well known in the western world during their lifetime.

Every anecdote relative to our heroine [d’Eon] has become a new subject of curiosity…In compliance with the request of our friends, no pains have been spared to procure every anecdote relative to Miss D’Eon de Beaumont that merits the public notice, and in order to convey a proper idea of the person of this lady, in whom we shall find a strange heterogeneous compound of male and female qualities, we obtained a striking resemblance of her face, from an original drawing…

Boston Magazine article on the Chevalière d'Eon, June 1784

This article on the Chevalière d'Eon was published for British and American readers. The article claims that d'Eon's biological sex was female and that they had lived as a man for years before revealing their true identity. In reality, d'Eon was assigned male at birth and began to live openly as a woman in middle age, after a successful career in the French military and government.

Boston Magazine operated from 1783 to 1786 as a publication created by a society of prominent Boston men and clergy. The magazine aimed to offer readers a combination of literature, political commentary, and refined entertainment. This particular article appears to be a reprint from an article that appeared in London Magazine in 1777. The title is misleading; although it includes "memoirs" in its title, it was not written by d'Éon.

The extraordinary personage who has been known in London, and many other parts of England, by the name of the Chevalier D’Eon ever since the year 1763…having been finally discovered to be a woman, by authentic, indubitable evidence given in the court of King’s Bench, at a trial…At what time she first appeared in the habit of a man, or what were the motives for so extraordinary a disguise, no person has been able to ascertain upon proper evidence; all that has been circulated in public, is founded upon conjecture…But all we can depend on as authentic is, that…for her personal bravery…she was honoured with the royal and military order of St. Louis, the cross of which order she constantly wore in England, pendant from a ribbon fastened to a button hole of her coat.

Zoom In

Zoom In

Glossary:

Chargé des affaires du France: French for a person charged with business, often serving as chief diplomat in the Ambassador’s absence.

le croix de St. Louis: French order of chivalry awarded to people for their bravery in the military

La habit des dames: ladies’ clothing

L’habit d’Homme: men’s clothing

Nabby Adams writes to her brother, John Quincy Adams, from France, about the Chevalière d'Eon, 1785

Abigail “Nabby” Adams, pictured on the left, was the oldest child of John and Abigail Adams. In this 1785 letter, she writes from France to her brother John Quincy Adams. Members of the Adams family were stationed overseas while John Adams represented the newly formed United States of America. The letter discusses Nabby’s desire for correspondence from John Quincy and her anxieties about communication difficulties. The quote below is excerpted from the end of the letter. Here, Nabby discusses the “famous Mademoiselle d’eon,” also known as Charlotte d’Éon de Beaumont, Charles d’Éon de Beaumont, but usually referred to as the Chevalière d’Éon (1728-1810). Her “matter-of-fact” description suggests that gender non-conformity may have been widely known in the educated and elite circles of European and possibly American societies.

Pray did you ever hear of the famouss Mademoiselle d'eon, who served as Chargé des affaires du France and afterwards as ambassador from that Court to this—who obtained le croix de St. Louis, and was in several engagements who fought two Duels on the part of some Ladies, and many more extrordinary matters—whose works, make thirteen vollumes &c. She has lately arrived in this City, and these Gentleman had dined with her and were speaking of her. She has resumed la habit des dames, but Mr. D. told me he was sure, She might go dressd in l'habit d'Homme and not be noticed, but she could not as a Lady. She wears her croix de St. Louis and as one may well suppose a singular figure, as well as an extrordinary Character.

Background Reading

Deborah Sampson Gannett: A Revolutionary War Hero

Women dressing as men was not as uncommon as one might think in Revolutionary America. Indeed, narratives of people assigned female at birth donning masculine attire and engaging in male-dominated occupations were prevalent in early modern Europe and Colonial America. This transgression of traditional gender roles was often driven by economic necessity and a desire for personal autonomy. This was even truer in times of war. As men fought, the women left behind stepped out of the confines and strictures of the private domestic sphere and became engaged in more public, more traditionally masculine roles. For example, during the American Revolution, some highborn women in Boston formed a “Committee of Ladies” to question suspected Tory women, while women of lesser privilege engaged in any work that could sustain their households. Some even served in the Continental Army.

One of the more famous cases in American History is the story of Deborah Sampson Gannett, whose life challenges the boundaries of gender in Revolutionary America, illustrating the opportunities and constraints faced by women during this time. Deborah Sampson was born in 1760 near Plymouth, Massachusetts. After the loss of their father, Sampson’s mother sent them away to first live with a cousin, and then with a pastor’s wife. At age 10, they became an indentured servant to Deacon Benjamin Thomas, a farmer in Middleborough, Massachusetts. Throughout their time in servitude, they acquired skills in domestic arts. In addition, Sampson worked in the fields, fed the animals, performed carpentry tasks, and participated in other work typically assigned to men. At 18, they left the Thomas household and worked as a teacher and weaver.

At the age of twenty-two, Sampson joined the Continental Army under the name of Robert Shurtliff, most likely for the signing bounty of “sixty pounds.” One newspaper in 1784 quoted an officer: Sampson “always gained the admiration and applause of her officers … [and] displayed herself with activity, alertness, chastity and valour.” All accounts point to a dedicated, honorable, and gallant soldier. Wounded by a bullet at the Battle of Tarrytown (New York), Sampson feared discovery and did not seek medical attention. Four months later, they were likely shot and developed “brain fever.” While in the hospital, the doctor discovered their secret. It is unclear whether this doctor revealed Sampson’s biological sex. They were honorably discharged from the Continental Army on October 25, 1783.

Sampson returned to Massachusetts in 1783. Some records indicate Sampson took the name of their younger brother, Ephraim, and continued wearing men’s clothing for a bit. They eventually met and married a local farmer, Benjamin Gannett, and bore three children with him – Earl Bradford, Mary, and Patience, and adopted a fourth, Susannah Shepherd. Farming was a hard life, and with four children to feed and clothe, the family needed money. In the late 1790s, publisher Herman Mann offered Sampson Gannett compensation to write their story under the title The Female Review: or, Memoirs of an American Young Lady (Source 2). Up until this point the story of Sampson Gannett was unknown to but a few; after the publication and subsequent lecture tour, Sampson Gannett’s story would spread throughout the newly formed nation.

In her research on early American fiction and the portrayal of women as national symbols, scholar Judith Hiltner notes that Herman Mann aimed to construct an emblem of “national virtue” from the “raw material of a cross-dressing female soldier.” The Female Review discussed Sampson Gannett’s time in the army; it also included titillating interactions with women, leading some to gossip about Sampson Gannett’s sexual partners during the war. While the book is almost universally understood to be a romanticized tale of Sampson Gannett’ life, one filled with many tall tales, scholars have been able to verify many of the facts, dates, names, and places mentioned.

What is more interesting is how well the book and lecture circuit were received by the public. The nation seemed hungry for the story of Deborah Sampson Gannett. While Mann wrote the original script for the lecture, Sampson Gannett made it their own, eventually donning their full Continental Army uniform and performing military maneuvers onstage while regaling the audience with stories of battles, becoming friends with Paul Revere, and meeting General John Patterson. According to scholar Jen Manion, Sampson Gannett’s role in the Continental Army “was celebrated and normalized,” and the press “characterized their actions as evidence of women’s contributions to the nation’s founding.”

This newfound celebration served an additional purpose. It allowed Sampson Gannett to petition the federal government for a pension. They were already receiving one from Massachusetts since 1792. At the turn of the century, they began to experience health issues and petitioned the Federal government for an invalid soldier’s pension. At that time, the Federal government was concerned about fraudulent claims; a former soldier needed to provide substantial evidence and documentation of injuries sustained during the war to receive a pension. Since Sampson Gannett concealed most of their wounds from doctors, they had little to support their case. Sampson Gannett enlisted the help of Paul Revere (Source 3), who aided in this endeavor by sending an appeal to William Eustis, a member of Congress from Massachusetts, on February 20, 1804. By 1805, Sampson Gannett was listed as receiving a disability pension. Sixteen years later, they were able to secure a “general service pension” from the Federal government.

In 1826, Deborah Sampson Gannett passed away. Their husband received spousal pay as the husband of a soldier, possibly the first recorded instance of this type of payment in US history. The committee in charge of these awards wrote that the Revolution “furnished no other similar example of female heroism, fidelity and courage.”

Chevalière d’Éon: Diplomat, Soldier, Spy

The story of the Chevalière d’Éon is remarkable. Born Charles Genevieve Louis Auguste Andre Timothee d’Éon de Beaumont in 1728, some historians consider d’Éon one of the first known cases of a person assigned male at birth living openly as a female in public. This remarkable French aristocrat lived two distinct lives—first excelling as a male diplomat, soldier, and secret agent, earning recognition for their diplomatic achievements and receiving the prestigious Cross of St. Louis for their valor as a Dragoon officer. Then, at the age of 49, d’Éon lived the last decades of their life as a woman. What makes d’Éon’s story truly extraordinary is not just the openness with which they lived their life but also the seeming acceptance of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century societies in which they lived.

Born to a noble but low-income family in Tonnerre, a small town in Burgundy, d’Éon excelled academically, having attended College Mazarin in Paris. After graduating, they published two well-regarded books on finance, became a Royal Censor, and eventually joined the diplomatic corps for the French government. Their first mission was as secretary to the Chevalièr Douglas at the Russian Court. Several sources, including d’Éon’s biography, suggested that it was during this period that d’Éon chose to wear women’s clothing as a clever way to gain access to the Russian Empress Elizabeth, who, until then, had not welcomed any of the male envoys sent her way previously. Without a historical actor directly stating their intention, it is impossible to know exactly why d’Éon wore women’s clothing, but one consideration could also be that they wanted to fulfill their own self-conception of gender. It was also around this time that d’Éon became a member of King Louis XV’s Secret du Roi (the King’s Secret), a spy ring that pursued aggressive foreign policies on behalf of the king, at times conflicting with the French government. Their next diplomatic post was in England, where the Court of St. James’s took an immediate liking to the charismatic diplomat. Though d'Éon began as a junior diplomatic officer, their charismatic personality so impressed King George III that Louis XV promoted them to Minister Plenipotentiary—effectively making d'Éon France's official representative in England while awaiting the arrival of a permanent ambassador. Simultaneously, the French King entrusted d'Éon with overseeing all Secret du Roi operations in England, combining their official diplomatic duties with covert intelligence work.

When d’Éon was eventually recalled to France due to a series of disagreements with the new French ambassador, d’Éon resisted, even going so far as to publish a book of their secret diplomatic correspondence. They also threatened to release more secret documents, which would essentially spark a war between France and England. They were essentially living in London in exile until 1774 when the new king, Louis XV allowed d’Éon to return, but only if they dressed as a woman, to “re-adopt” women’s clothing, implying that the King believed d’Éon to have been a female who has worn men’s clothing for most of their early life. This assumption was commonplace among the upper echelons of French society and would eventually become an accepted fact in European and North American societies. The King also paid d’Éon an annual pension of 12000 livres per year for the documents. By legally recognizing d’Éon as a woman, the King also closed off any chances for future advancement in the diplomatic corps or the Royal Court, potentially avoiding future scandals.

Upon return to France in the 1770s, d’Éon lived openly as a woman until their death. Rumors and gossip had spread that d’Éon was, in fact, a woman all their life and that for the first 49 years of their life, they had lived as a man for the sake of opportunity and advancement. When the French Revolution took place in 1789, d’Éon lost their pension and family land and supported themselves through fencing exhibitions while dressed as a female. The Chevalièr d’Éon died on May 21, 1810, having been essentially bedridden for the past three years and living in relative poverty. It was only upon their death that it was revealed they possessed male genitalia.

Historian Greta Lafleur notes that d’Éon’s tale was likely well-known in England, France, and even North America, with many books and news articles published during d’Éon’s lifetime. Boston Magazine reprinted a drawing of the “Mademoiselle de Beaumont or the Chevalièr D’Eon” in its June 1784 edition (Source 4). The engraving pictures d’Éon wearing both male and female clothing, mockingly challenging their identity in a manner that modern society would find problematic and unacceptable. However, for many in the eighteenth century, they would have viewed d’Éon as an oddity. The next source (Source 5) is an article recounting how “D’Eon” was “finally discovered to be a woman, by authentic, indubitable evidence.” Maybe Abigail “Nabby” Adams read a version of this article while in Britain with her father, John Adams, who was serving as the First Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of St. James’s. Nabby recounted what she had heard of the “famous Mademoiselle d’eon” in a December 1785 letter to her brother, future president John Quincy Adams (Source 6). She recounted what she had heard of d’Éon’s exploits – fighting duels, wearing clothing of both sexes, and how they were the recipient of the “croix de St. Louis.”

Glossary

Chevalièr (masculine form) & Chevalière (feminine form): French titles equivalent to an English knight or dame.

College Mazarin: A historic college at the University of Paris, founded in 1667.

Court of St. James’s: The official royal court for the sovereign of the United Kingdom.

Cross of St. Louis: The Cross of St. Louis was a dynastic order of chivalry awarded to officers of exceptional quality. Analogous to an English knight.

Dragoons: A mounted soldier in the French army who could fight both on horseback and while dismounted.

Minister Plenipotentiary: A diplomatic official who had the full power to act on behalf of the French monarch.

Royal Censor: A person responsible for examining and approving all published texts.

Close Reading Questions

Miss Betty Cooper self-liberation newspaper ad

- To “read against the grain” is to challenge the dominant reading of a text, questioning the beliefs and attitudes of the author and looking for what is left out or hidden. What can we know about Miss Betty Cooper from the dominant reading of the text, i.e. how she is described by her former enslaver in this advertisement? What can we learn or question about Miss Cooper when we read against the grain for what is left out or unsaid?

- What might it mean that Miss Betty Cooper is “well known” by this name in Boston?

- After reading Dr. Hopkins’ article, compare and contrast the names “Cato” and “Miss Betty Cooper.” What kinds of meanings does each name carry? How do both names relate to gender differently? Why might Cooper have chosen that name for herself?

- According to Dr. Hopkins, while this advertisement can’t tell us how Miss Cooper defined her own identity and why, it does suggest that she “transgressed gender boundaries in ways that can be understood both within a larger transgender history and in the specific context of Black resistance to colonizer’s ideas about gender.”

Deborah Sampson Gannet sources

- Why might a person assigned female at birth choose to enlist as a soldier in a war effort?

- What risks do you think Shurtliff (Sampson) faced during their time in the army?

- How did the publication of The Female Review (Source Two) shape public perceptions of Deborah Sampson Gannett? For what purpose?

- How does Paul Revere's letter (Source Three) help us understand Sampson Gannett's reputation as a war hero?

- Paul Revere's 1804 letter (Source Three) emphasizes Sampson Gannett's qualities as a "dutifull Wife and affectionate parent" alongside their military service. Why might he have chosen to highlight these traditional feminine roles when advocating for their pension?

- According to the 1784 newspaper quote, Sampson Gannett "always gained the admiration and applause of her officers" and "displayed herself with activity, alertness, chastity and valour." How does this contemporary assessment complicate modern assumptions about women's capabilities in combat roles?

- Why do you think some historians disagree about aspects of Sampson Gannett’s life? What does this tell us about historical sources and interpretation?

- What challenges do historians face when relying on accounts written by other people about a historical actor?

Chevalière d'Eon sources

- Using Boston Magazine’s engraving (Source 4), consider the following questions:

- What do you think the engraver’s motive or purpose was in creating this?

- What does the choice in clothing tell us about rank, nobility, honors, and status?

- Who do you think was the intended audience? How might that have influenced the engraver?

- How does this image navigate the tension between d’Éon’s feminine presentation and their previous masculine roles of authority?

- The Boston Magazine (Source Five) article mentions that d’Éon was “finally discovered to be a woman” from a court trial. How does this legal “proof” contrast with what we know happened after d’Éon’s death? What does this suggest about how gender was understood and “proven” in the eighteenth century?

- What about d’Éon’s privacy? Was it violated? Did the public have a right to know this information? How does this relate to the politics of outing in contemporary society?

- What details does Nabby Adams (Source Six) find most noteworthy? Why do you think she shared them with her brother? What do you think her purpose and/or motive was? How does her description reflect the attitudes of American society?

- The Boston Magazine (Source 5) presents d’Éon’s story as a settled fact, while Nabby Adams’ letter (Source 6) portrays it as gossip and rumor. How do these different approaches to the same story affect what we can learn from each source?

- Is there any difference in tone, perspective, and word choice between the public description offered in Boston Magazine (Source 5) and the private one offered in Adams’ letter (Source 6)?

- Based on sources 4, 5 and 6, how would you characterize eighteenth-century society’s reaction to d’Éon’s gender expression? Do you think the seeming acceptance was universal or more nuanced? Did d’Éon’s noble birth and accomplishments affect this acceptance?

Additional reading on Betty Cooper

Secondary Source

- Dr. Caitlin G.D. Hopkins, “Well Known as Miss Betty Cooper”: Gender Expression in 18th-Century Boston – NOTCHES (2018)

- This article explores the newspaper ad about Betty Cooper and what it tells us about gender expression and identity in 18th century Massachusetts.

Additional primary and secondary sources on Deborah Sampson Gannet

Primary Sources

- Petition Testimony of Deborah Sampson Gannett, 9/14/1818 | National Archives

- Full text of The Female Review | HathiTrust

Secondary Sources

- Bronski, Michael. A Queer History of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2012.

- Gundersen, Joan R. To Be Useful to the World: Women in Revolutionary America, 1740-1790. Chapel Hill, N.C: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Hiltner, Judith. “‘She Bled in Secret’: Deborah Sampson, Herman Mann and ‘The Female Review.’” Early American Literature 34, no. 2 (1999): 190–220.

- Kravitz, Bennett. “A Certain Doubt: The Lost Voice of Deborah Samson in Revolutionary America.” Studies in Popular Culture 22, no. 2 (1999): 47–60.

- Manion, Jen. Female Husbands: A Trans History. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2020.

- Young, Alfred F. Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, n.d.

Additional primary and secondary sources on Chevalière d'Eon

Primary Sources

- “The Gender Fluidity of the Chevalier d’Éon” | Art UK

- “The Libelous Letter of the Chevalier d’Eon” | National Archives UK

Secondary Sources

- Episode 19 - "Pray did you ever hear of the famous Mademoiselle d’eon?" Your Most Obedient & Humble Servant Podcast (2021)

- In this podcast episode, host Kathryn Gehred talks with Julia Ftacek, a scholar of transgender femininity in 18th century literature, about the Chevalier d'Eon and Nabby Adams letter, and what that tells us about gender expression and identity both in the past and today.

- Burrows, Simon, Jonathan Conlin, Russell Goulbourne, and Valerie Mainz, eds. The Chevalier d’Eon and His Worlds: Gender, Espionage and Politics in the Eighteenth Century. London New York: Continuum, 2010.

- Gary Kates, 'The Transgendered World of the D'Éon/Chevalière D'Eon', The Journal of Modern History, 1995.

- LaFleur, Greta, Masha Raskolnikov, and Anna Klosowska, eds. Trans Historical. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 2021.

- Manion, Jen. Female Husbands: A Trans History. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2020.

- McRobbie, Linda Rodriguez. “The Incredible Chevalier d’Eon, Who Left France as a Male Spy and Returned as a Christian Woman.” Atlas Obscura, July 29, 2016. http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-incredible-chevalier-deon-who-left-france-as-a-male-spy-and-returned-as-a-christian-woman.

- Orange, Mad. Transition: Captivating Portraits and Transgender Expression in 18th-Century France. Independently published, n.d.

Rotondi, Jessica Pearce. “The French Diplomat Who Lived as Both a Man and a Woman.” History.com, January 10, 2024. https://www.history.com/articles/chevalier-d-eon-french-spy-man-woman.