“The bitterness and violence of Presidential electioneering”: John Quincy Adams on the campaign trail, 1824-1828

Inquiry Question 1: How did presidential campaigns change over the course of the 1820s?

Inquiry Question 2: How did the presidential campaigns of 1824 and 1828 impact John Quincy Adams' career and legacy?

Background Reading for Students

John Quincy Adams describes negativity in the campaign of 1824 in his diary, 31 August 1824

John Quincy Adams wrote in his diary each day for 70 years. He regularly commented on the election of 1824 – his first campaign for President – in his entries.

During President Monroe’s second administration, members of his cabinet started vying for the 1824 presidential election; in addition to secretary of state John Quincy Adams, other contenders included William H. Crawford, Secretary of the Treasury, and John C. Calhoun, Secretary of War. Henry Clay, Speaker of the House of Representatives, and General Andrew Jackson, war hero, rounded out the list of competitors. Below is an excerpt Adams wrote in his diary during the 1824 campaign.

Diary Citation: John Quincy Adams digital diary, Vol. 35 Main Entry, 31 August 1824, p. 247, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Image Citation: John Quincy Adams, engraving by Francis Kearney, circa 1824, Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/459.

The bitterness and violence of Presidential electioneering increases as the time advances. The uncertainty of the event continues as great as ever. It seems as if every liar and calumniator in the Country was at work day and night to destroy my character— It does not surprize me; because I have seen the same species of ribaldry year after year heaped upon my father, and for a long time upon Washington…

Louisa Catherine Adams reflects on the role of the politicians' wives in a letter to John Adams, 22 December 1819

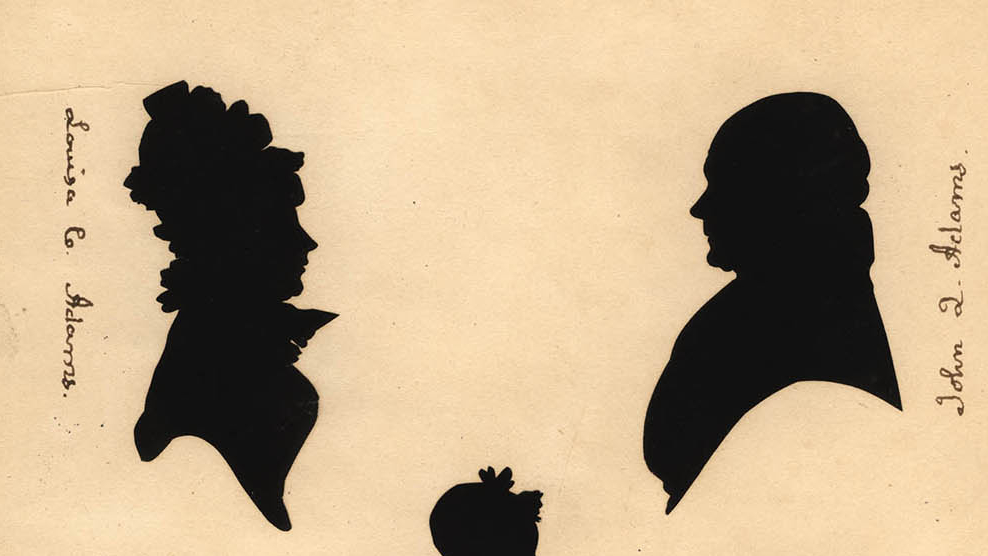

Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams (1775-1852), the wife of John Quincy Adams, was the United States’s first foreign-born first lady. She married Adams in London in 1797 and contributed to his diplomatic and political career through her skillful navigation of European courts and Washington social politics. She hosted parties, balls, and regular Tuesday “sociables” to gain the support of influential Washingtonians and, particularly, the congressmen who would be instrumental in determining the presidential election of 1824.

Once John Quincy Adams became secretary of state, a stepping-stone to the presidency, it became Louisa’s responsibility to promote, by social means, her husband’s goal of succeeding James Monroe. On January 8, 1824, Louisa Adams hosted a ball, in which Andrew Jackson was the guest of honor, on the anniversary of his victory at the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. What was thereafter remembered as the Jackson Ball honored Andrew Jackson as a national hero and, by association, brought John Quincy Adams into the spotlight of the 1824 presidential race.

Citations:

Image: Family of John Quincy Adams, Silhouettes by Master Henkes, 1829, From the Silhouette Collection, Adams Family Silhouette, Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/767.

Quote: Letter from Louisa Catherine Adams to John Adams, 22 December 1819 - 15 January 1820, Manuscript, from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/6892.

It is understood that a man who is ambitious to become President of the United States must make his wife visit the ladies of the members of congress first, otherwise he is totally inefficient to fill so high an office. You would laugh could you see Mr A— every morning preparing a set of cards with as much formality as if he was drawing up some very important article in a commercial treaty.

- Louisa Catherine Adams in a letter to her father-in-law John Adams, December 22, 1829 - January 15, 1820

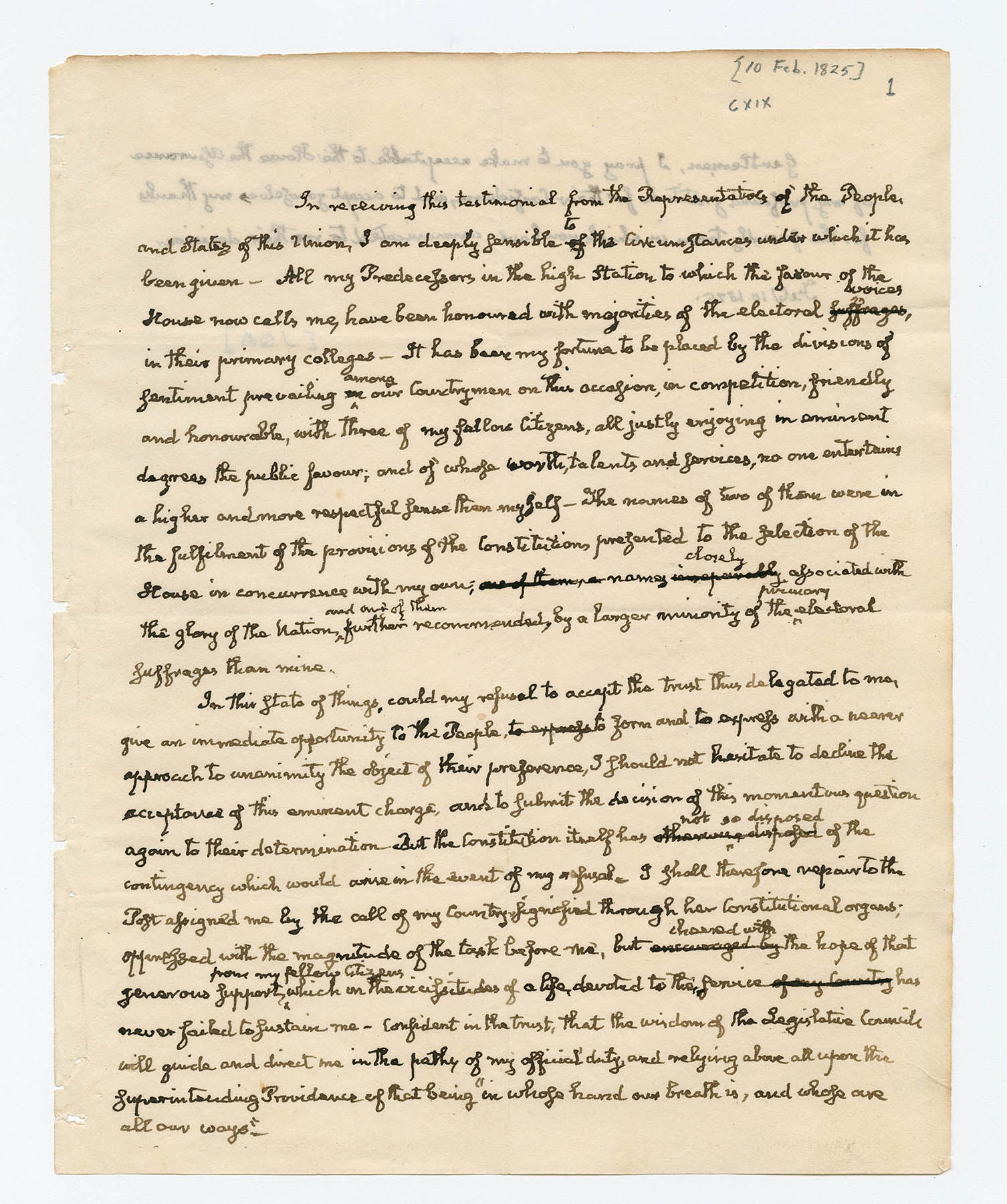

John Quincy Adams drafts his acceptance of the Presidency from the House of Representatives, 10 February 1825

Even though Jackson won the popular vote in the 1824 election, no candidate received enough electoral votes to become President, so the U.S. House voted on the winner. John Quincy Adams was elected over Jackson on the first ballot. On February 10, 1825, Adams drafted this document for the members of the U.S. House of Representatives in response to a committee of House members who visited him earlier that day to personally notify him that the House had, on February 9th, chosen him to be the next president.

Citation: Statement from John Quincy Adams to the Committee of Notification of U.S. House of Representatives (draft), 10 February 1825, from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/6837.

In receiving this testimonial from the Representatives of the People and States of the Union I am deeply sensible of the Circumstances under which it has been given – All my Predecessors in the high station to which the favour of the House now calls me have been honored with majorities of the electoral voices, in their primary colleges…

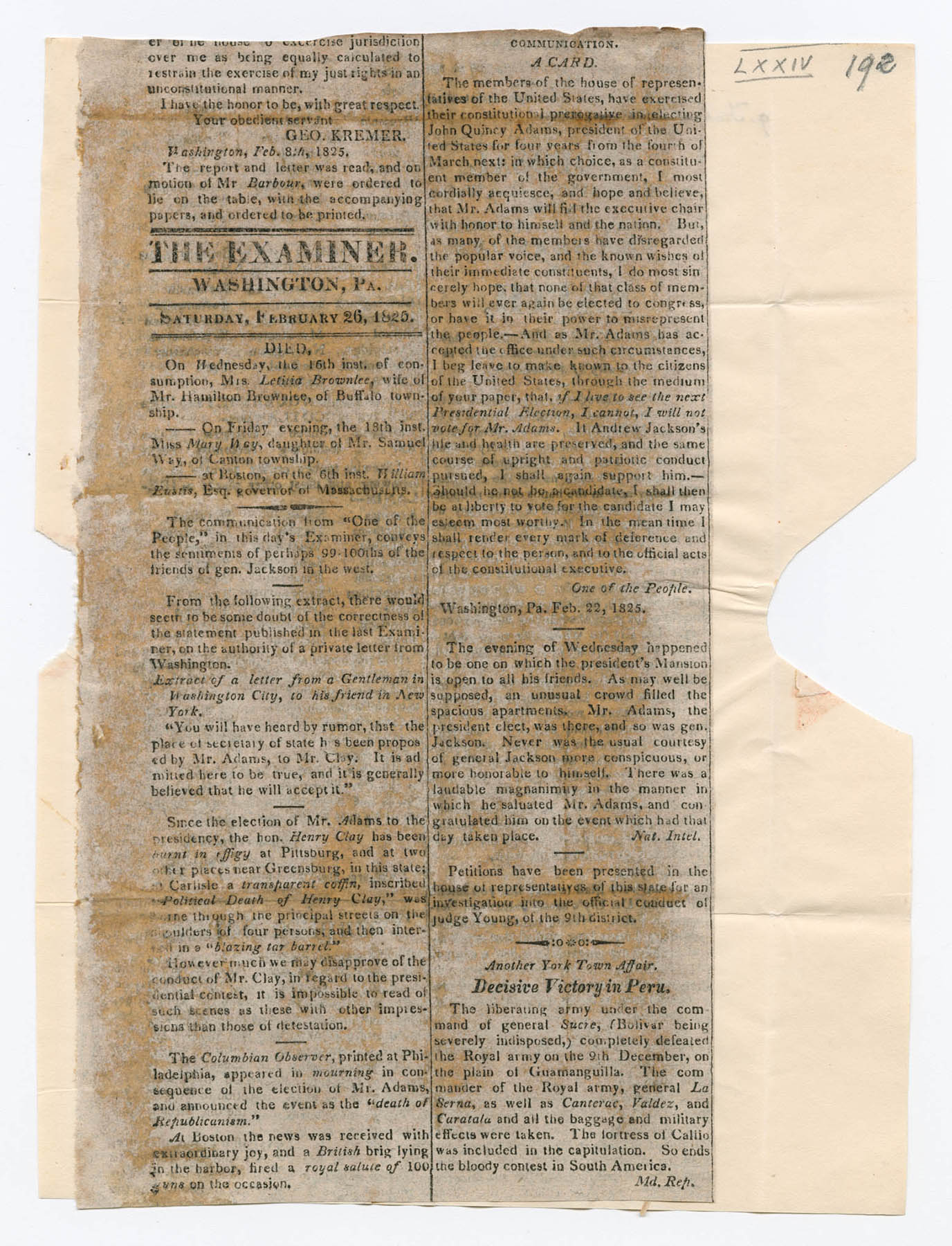

Public perception of a ‘corrupt bargain’ leads to anger against Adams and Clay, 26 February 1825

William Hill Wells was a Federalist politician from Delaware, but by 1824, was no longer serving elected office. On February 26, 1825, Wells wrote a letter to JQA after Adams was named to the Presidency. In the letter, Wells says that another Delaware politician, Rep. Louis McLane – a nominal federalist, but vocal opponent of Adams and Clay and supporter of Jackson – was influencing the Delaware Gazette newspaper to print negative stories about Adams and Clay. Wells included a newspaper clipping in his letter that featured letters to the editor of the Washington Examiner, a Pennsylvania newspaper, showing an outpouring of public anger toward Adams and Henry Clay due to the belief that there had been a corrupt bargain between the two men.

Citation: Letter from William Hill Wells to John Quincy Adams, 26 February 1825, and enclosure, from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/6891.

Since the election of Mr. Adams to the presidency, the hon. Henry Clay has been burnt in effigy at Pittsburg, and at two other places near Greensburg, in this state; [in] Carlisle a transparent coffin inscribed "Political Death of Henry Clay," was borne through the principal streets on the shoulders of four persons, and then the interred in a ‘blazing tar barrel.’

- Anonymous quote from a letter to the editor of the Washington, PA Examiner, signed 'One of the People'

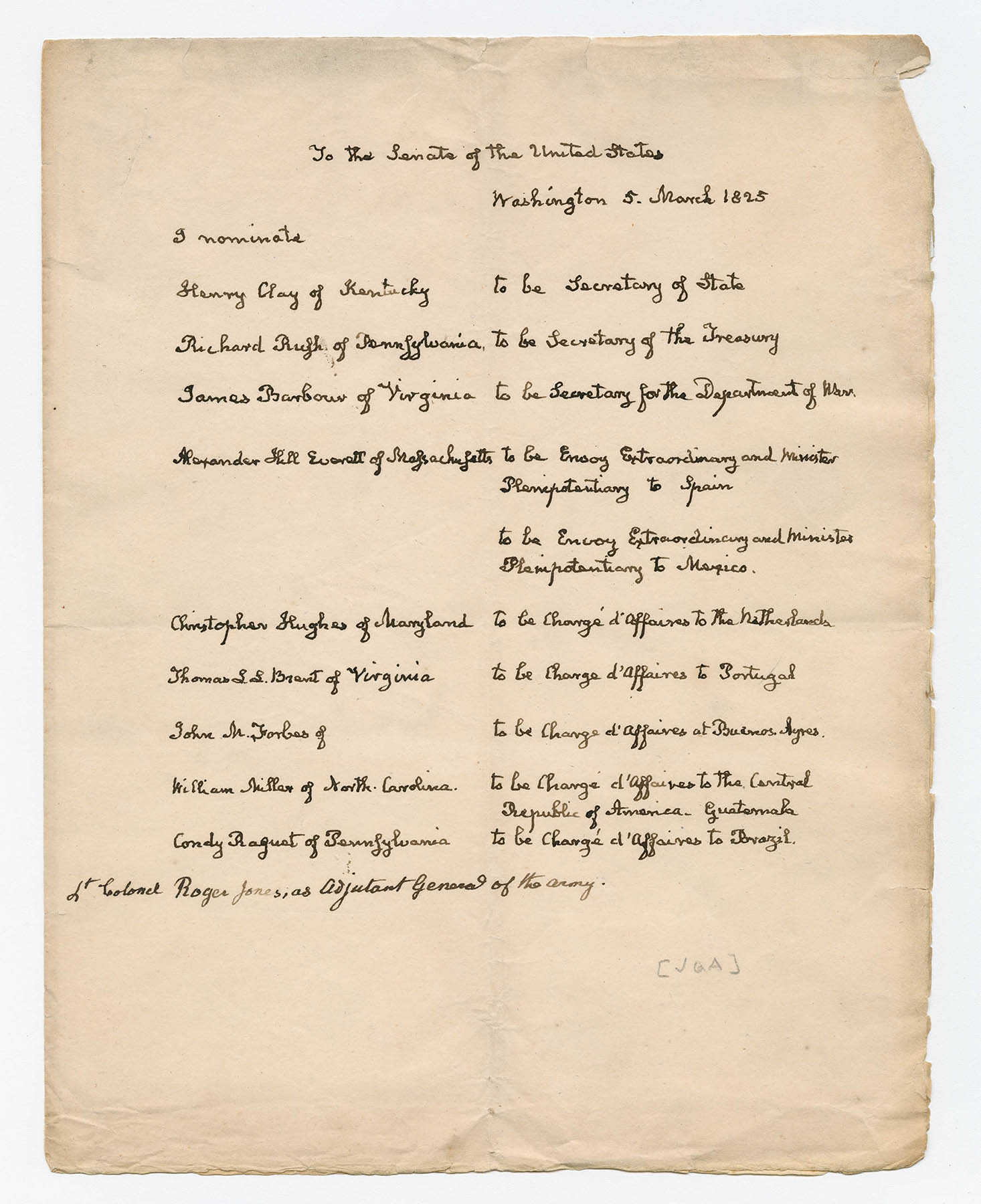

John Quincy Adams nominates his cabinet and diplomatic officials, 5 March 1825

On March 5 1825, President-elect John Quincy Adams submitted his list of nominations to his cabinet to the U.S. Senate. Adams nominated Henry Clay of Kentucky to fill his previous role as Secretary of State. Seen as a stepping stone to the presidency, Secretary of State was a coveted role and members of Congress and the general public immediately began to accuse Adams and Clay of having made a “corrupt bargain” alleging that Clay, in his role as a Congressman and Speaker of the House, voted for Adams to be President because Adams had already promised him Secretary of State if he won the election. Adams and Clay would always deny the allegations, but the public perception of the bargain would haunt both of their political careers.

Citation: Nominations of cabinet/diplomatic officials (list) from John Quincy Adams to the U.S. Senate, 5 March 1825, Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/6846.

To the Senate of the United States

Washington 5 March 1825

I nominate

Henry Clay of Kentucky to be Secretary of State

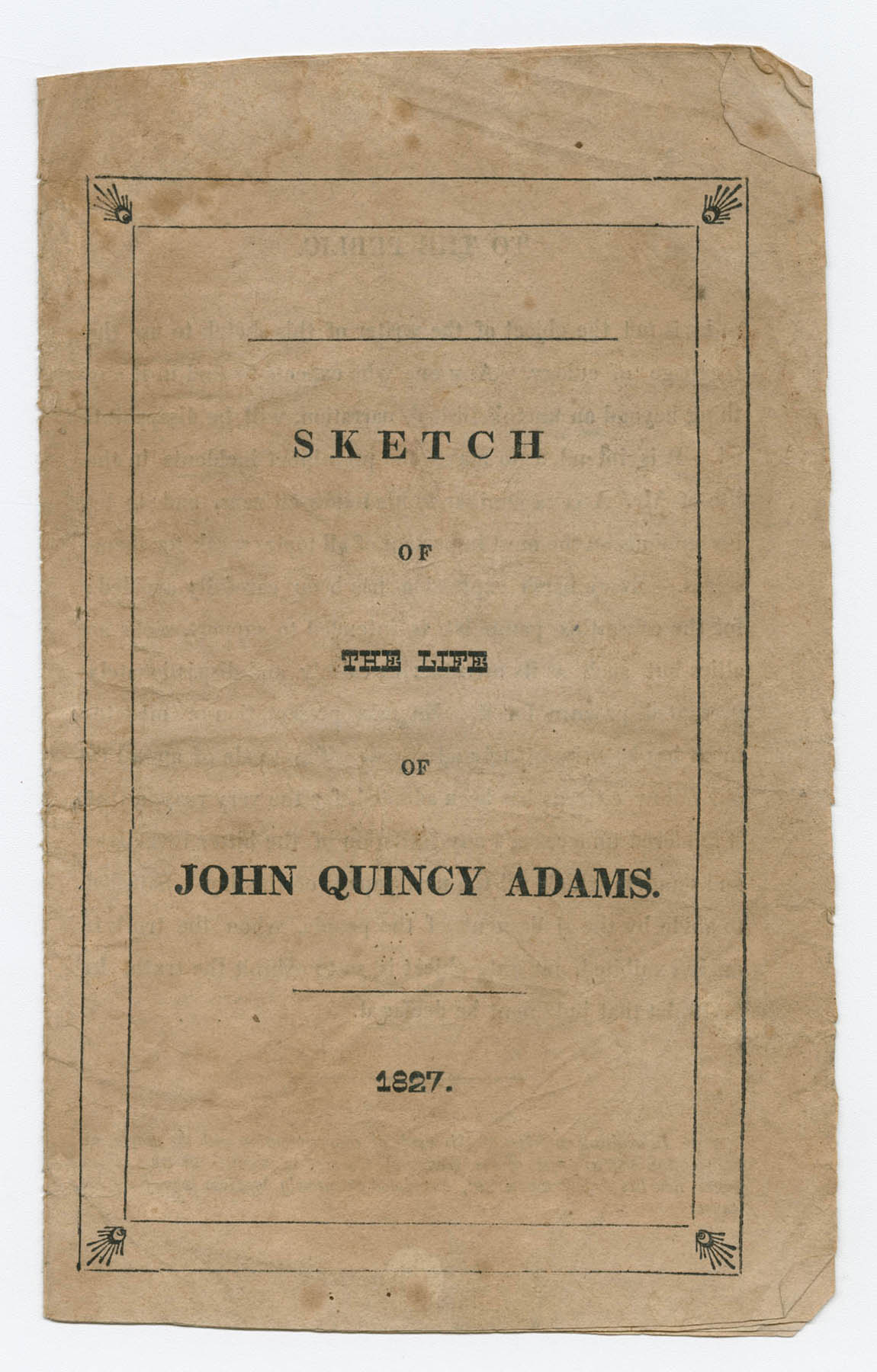

John Quincy Adams writes one of the first campaign biographies (about himself)

John Quincy Adams was one of the first people to write and publish a biography as part of his campaign for president. He and his father, John Adams, wrote and published a Sketch of the life of John Quincy Adams together in 1824. Although John Quincy Adams was the son of the second President of the United States, he used his campaign biography to portray himself as a man of the common people. Hoping it would be read widely, on the last page of the short biography the Adamses encouraged readers to “Lend this pamphlet to your neighbor.”

In 1827, Adams re-published a Sketch of the Life of John Quincy Adams when he was running for re-election. The inside cover of this edition speaks directly to his audience, the American public, and states its purpose: "This mode of appeal to our fellow citizens has been adopted, for the very reason, that it rendered unnecessary any imitation of the bitter invectives and slanders which fill the newspapers of the day." Adams thus used his campaign biography to present his own view of himself and his policies.

Citation: Sketch of the life of John Quincy Adams. 1827. Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/6895.

John Quincy Adams is descended from a race of farmers, tradesmen, and mechanics…. The principles of American Independence and Freedom, were instilled into the mind of John Quincy Adams, in the very dawn of his existence.

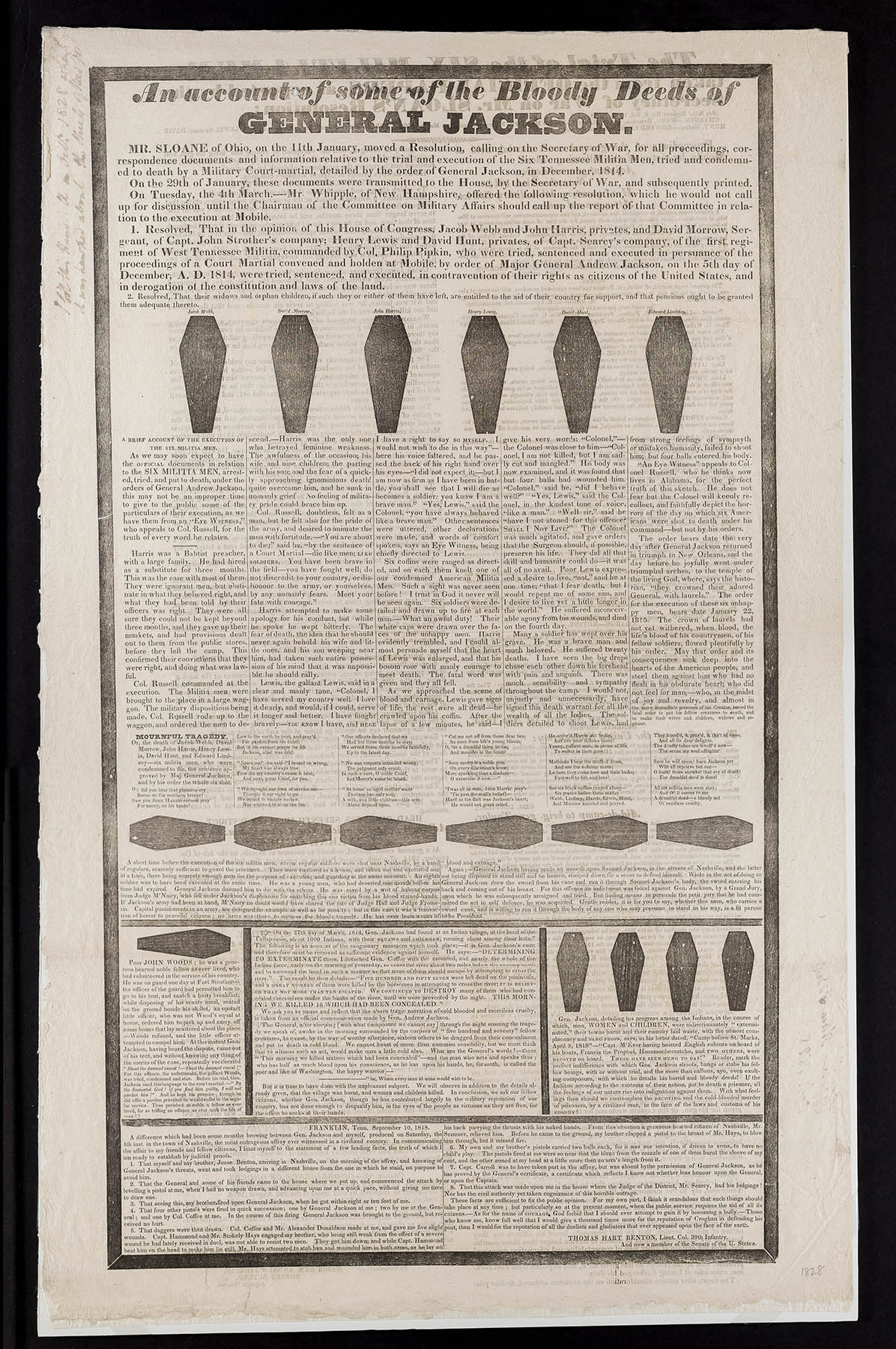

Coffin Handbill attacks Andrew Jackson's military record, 1828

The 1824 presidential election saw fierce “electioneering”—campaigning today—by political operatives, but not by the candidates themselves. Campaign literature largely sought to promote one candidate while avoiding serious personal attacks on the opposition. Four years later, a rematch between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson in the 1828 election ushered in a new era of political mudslinging by their supporters. This 1828 coffin handbill is a prime example of an election attack ad. Where JQA had once defended Jackson’s military campaigns during the War of 1812, the coffin handbills directly attacked General Jackson’s war record for cruelty towards his own soldiers and Creek and other Native American civilians.

Jackson's supporters, on the other hand, continued to tout Jackson's military record and his political policies with campaign tokens such as this one depicting him on a horse.

Citation: An account of some of the bloody deeds of General Jackson, broadside, [United States? 1828?], Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/6894.

An Account of some of the Bloody Deeds of GENERAL JACKSON

'Gentle reader, it is for you to say, whether this man [Andrew Jackson], who carries a sword cane, and is willing to run it through the body of anyone who may presume to stand in his way, is a fit person to be President.'

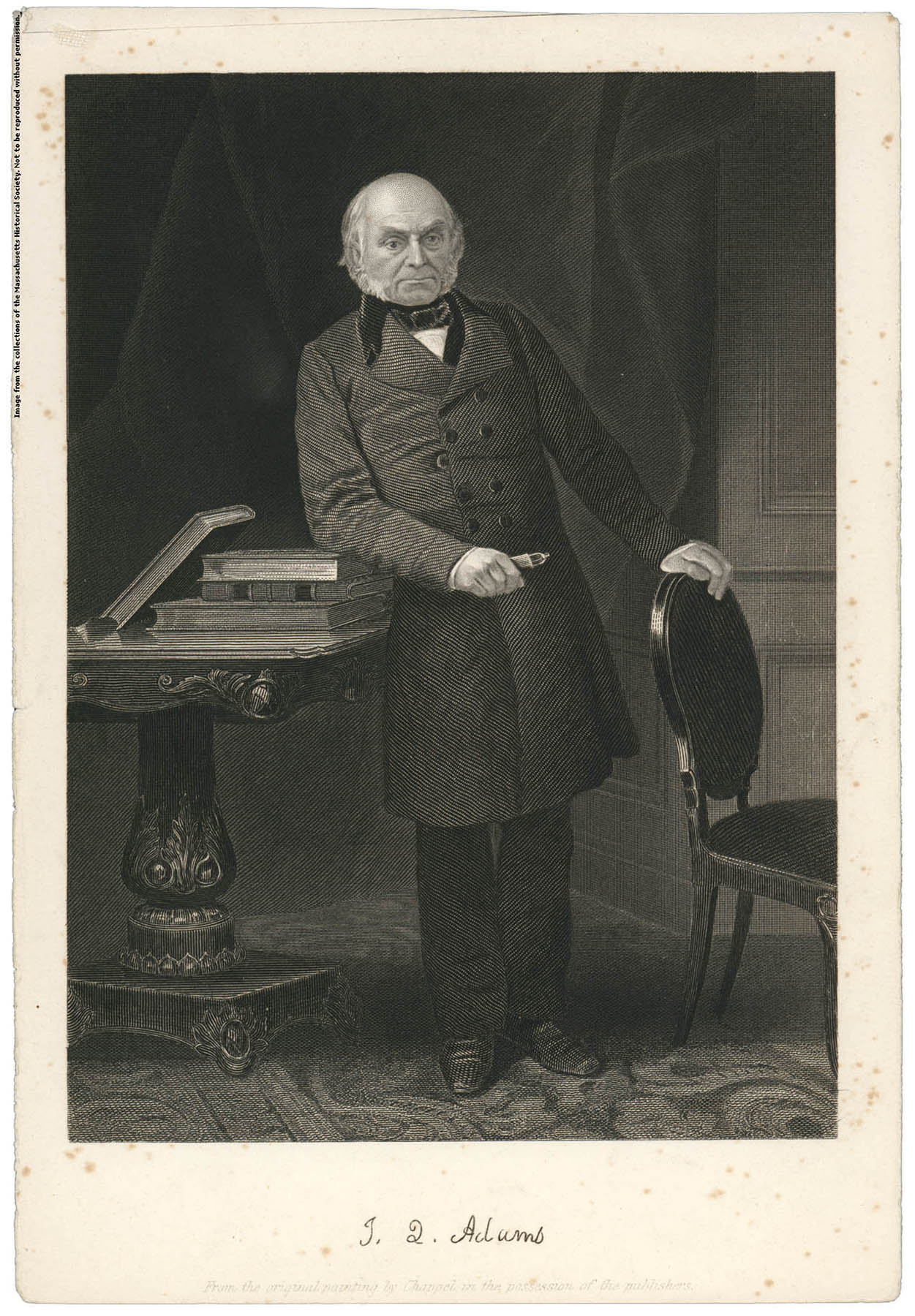

Congressman John Quincy Adams reflects on the lasting power of the idea of a ‘corrupt bargain,’ 30 April 1844

John Quincy Adams had foreseen that the public’s belief in a ‘corrupt bargain’ would lead him to lose the election of 1828 to Andrew Jackson, and he was right. Nonetheless, Adams and Clay continued to serve elected office. In 1830, Adans was elected to the House of Representatives and served there for the remaining sixteen years of his life. In the presidential election of 1844, James K. Polk narrowly defeated Henry Clay. Although slavery and the annexation of Texas were the major issues, the supposed "corrupt bargain" of 1824 was also brought up on the campaign trail.

In his diary on April 30, 1844, Adams wrote about the legacy of the election of 1824.

Citations:

Image: John Quincy Adams, Woodcut of a painting by Chappel, from Portraits of American Abolitionists (a collection of images of individuals representing a broad spectrum of viewpoints in the slavery debate), Photo 81.4, Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/831.

Quote: John Quincy Adams digital diary, Volume 44, 30 April 1844, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[Congressman] Linn Boyd of Kentucky…turned off to his new vamped old slander of a corrupt bargain between Henry Clay and me…This stale and base columny, already abandoned and recanted by those who first invented and imposed upon the credulity of their partizans these men are now blowing the coals up to kindle again into a flame to consume Clay’s election hopes and my honest fame.

Background Reading

Historical Overview

John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), son of John Adams and Abigail Smith Adams, served as the sixth president of the United States. A young child at the outbreak of the American Revolution, John Quincy accompanied his father to Europe in 1778 at age ten, living first in Paris and then Amsterdam. As a teenager, he traveled with Francis Dana to St. Petersburg, Russia, where he served as Dana’s secretary and French interpreter. Returning to the United States in 1785, Adams attended Harvard University and trained to become a lawyer like his now famous father.[1]

After opening his law practice in Boston, John Quincy began writing essays in local newspapers under various pseudonyms (“Publicola,” “Menander,” “Marcellus,” and “Columbus”) to express his political views. Before long, though, a young but worldly Adams was back in Europe. In 1794, President George Washington appointed him resident minister to the Netherlands; in 1797, his father (now President Adams) sent him to Berlin as minister plenipotentiary to Prussia.[2]

Returning once again to the United States in 1801, John Quincy served in the Massachusetts state senate from 1802 to 1803 and the U.S. Senate from 1803 to 1808.[3] He was also named the first Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard University.[4] Soon he was abroad again, this time as minister plenipotentiary to Russia, where he lived for almost five years from 1809 to 1814.[5] Adams was sent to Ghent in 1814 to head the commission negotiating the Anglo-American peace treaty that ended the War of 1812.[6] President James Madison then appointed John Quincy envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to Great Britain, where he served from 1815 to 1817.[7]

With decades of diplomatic experience, it was no surprise when President James Monroe appointed John Quincy Adams his secretary of state. Adams served in this role with distinction for eight years, from 1817 to 1825. His impressive accomplishments include the signing of the Adams-Onís Transcontinental Treaty, which settled the boundary between the United States and Mexico and transferred Florida to the United States. Adams also developed the so-called Monroe Doctrine, which established the Western hemisphere as a “sphere of interest” for the United States, warning European countries against future interference in the Americas.[8]

ELECTION OF 1824

Five men sought the presidency in 1824. John Quincy Adams, now secretary of state—at that time a stepping-stone to the presidency—very much wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps and become president. Two other members of President Monroe’s cabinet, Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, likewise sought the office. So did Henry Clay, Speaker of the House of Representatives, and General Andrew Jackson, war hero remembered for his victory at the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812.[9]

All five presidential candidates called themselves Democratic-Republicans—the opposing Federalist Party was no longer influential at the national level. Though associated with the same political party, these presidential contenders did not share a unified ideology; in fact, each held slightly different views on tariffs, internal improvements, banking, public land policy, and slavery. There was no formal “platform” for the Democratic-Republican Party at the time.[10]

The presidential campaign was contentious. John Quincy commented on it in his diary in August 1824: “The bitterness and violence of Presidential electioneering increases as the time advances. The uncertainty of the event continues as great as ever. It seems as if every liar and calumniator in the Country was at work day and night to destroy my character.” (Source 1) Adams rarely responded to accusations in newspapers, however. It would be “an endless task,” he wrote, maintaining that “the tongue of falsehood can never be silenced: and I have not time to spare from public business to the vindication of myself.” Instead, to promote his candidacy, Adams pioneered the use of the campaign biography, publishing (with his father’s help) “Sketch of the Life of John Quincy Adams.” (Source 6) In it, Adams downplayed his extraordinary background, declaring himself “descended from a race of farmers, tradesmen, and mechanics.”

It was Andrew Jackson who received the most popular and electoral votes in the presidential election of 1824, but, with votes split between the candidates, he did not reach the necessary threshold to win. The Twelfth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution directs that in such instances the House of Representatives chooses the president with each state having one vote. As dictated in the Constitution, the House would consider the three candidates who received the most electoral votes: Jackson, Adams, and Crawford. Fourth-place finisher Henry Clay, who had support from western states as well as congressional friends across the country, could now throw his influence behind another candidate—which turned out to be Adams. And so, even though Jackson had the most public support, the House of Representatives elected second-place finisher John Quincy Adams as the next President of the United States on February 9, 1825.[11] Adams was inaugurated the following month on March 4.

Adams understood keenly that the way he ascended to the presidency, though constitutional, was not ideal and did not necessarily represent the will of the American people. In response to his election, he wrote to members of the U.S. House, “All my Predecessors in the high station to which the favour of the House now calls me have been honored with majorities of the electoral voices, in their primary colleges.” (Source 3) Jackson and his supporters, for their part, felt that the election had been stolen and worked tirelessly to undermine John Quincy Adams and his agenda for the next four years.

CORRUPT BARGAIN

Shortly after the 1824 presidential election, an anonymous letter in a Washington, D.C., newspaper sparked rumors about a “corrupt bargain” that allegedly had been struck between John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay in which Clay agreed to support Adams for president in exchange for being named secretary of state. While Clay likely did engage in behind-the-scenes political maneuvering to push support toward Adams, there is no evidence of corruption. Both men always denied that there was an explicit arrangement.[12] After Adams’s presidency ended, Clay wrote to him: “So far was I, in voting for you as President, from being influenced by any personal or selfish consideration, that I felt and I stated, at the time, that, if I knew and disapproved every member of your Cabinet, I should still greatly prefer you to General Jackson.” Adams likewise stood by his decision to nominate Clay as secretary of state, insisting in 1830 that he still “believed him the man of the Union best fitted for the place.”

Adams and Clay were not close allies—Adams thought Clay an excellent and ambitious politician, if “only half educated” and having “loose” morals—but they were more similar ideologically than the other candidates, and it made sense that they supported one another politically. However, Jackson’s supporters were furious, attacking Clay in newspapers and even threatening him with violence. Though unproven, the widely-circulated and oft-repeated allegations of a “corrupt bargain” cast shadows on both Adams’s and Clay’s political careers and soured public perception of them for many years. When Clay ran for president against James K. Polk in 1844, an elderly Adams referred once again in his diary to the “old slander of a corrupt bargain between Henry Clay and me.” He lamented that “this stale and base columny, already abandoned and recanted” had been rekindled “into a flame to consume Clay’s election hopes and my honest fame.” (Source 8)

PRESIDENCY

John Quincy Adams’s one term as president was in many respects the low point of his political career. Intelligent and well-read, introverted and reserved, self-disciplined and principled almost to a fault, Adams excelled as a diplomat but struggled as president. Near the beginning of his administration he laid out an ambitious agenda: he wanted the federal government to support internal improvements and infrastructure, and he had plans for a national university, a naval academy, and the creation of a Department of the Interior.[13] In the end he accomplished very little, mostly because he faced overwhelming political opposition—especially after the 1826 midterm elections when Andrew Jackson’s supporters took control of Congress. While Adams and Jackson had been on good terms prior to the 1824 election—Adams even threw a ball for General Jackson in early 1824 and considered asking Jackson to be his running mate—their relationship deteriorated quickly following the presidential race. Less than a year into his presidency, Adams wrote in his diary that “a great effort had been made in both Houses to combine the discordant elements, of the Crawford and Jackson and Calhoun men into a united opposition, against the Administration.” In 1826, Adams’s vice president, John C. Calhoun, informed Jackson that he would support him—not Adams—in the next presidential election.[14]

ELECTION OF 1828

The election of 1828, a rematch between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, proved to be an absolutely brutal campaign in which both candidates (and their wives, Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams and Rachel Donelson Jackson) were personally attacked by the opposing side. In addition to accusations of corruption surrounding the 1824 election, there was criticism of Adams being “educated a monarchist” and being “hostile to popular government.” Perhaps the most extreme political smear Adams faced was that he acted as a pimp for Alexander I while living in Russia, supposedly brokering a relationship between the czar and an Adams servant.[15] Adams, shocked, declared this an “infamous calumny” and a “new form of Slander.” As he summarized February 1829 in his diary, he concluded that there was a “combination of parties, and of public men, against my character and reputation such as I believe never before was exhibited against any man since this Union existed— Posterity will scarcely believe it.”

In 1828 Andrew Jackson won by a landslide, with 178 to Adams’s 83 electoral votes.[16] Adams would be a one-term president, just like his father. Adams grieved: “The Sun of my political life sets in the deepest gloom.” Exhausted and angry, he refused to attend Jackson’s inauguration. Five years later, when Jackson received an honorary degree of Doctor of Laws from Harvard, Adam refused to attend that too. “The personal Relations in which President Jackson had chosen to place himself with me,” Adams declared, “were such that I could hold no intercourse of a friendly character with him.”

POST-PRESIDENTIAL CAREER

Two years after Adams’s defeat, Massachusetts sent him back to Washington D.C., this time as a congressman. John Quincy Adams went on to serve in the House of Representatives for eighteen years.[17] During this time he advocated for an end to the “gag rule” that prevented congressional discussion or consideration of antislavery petitions, achieving its repeal in 1844.[18] He also successfully defended the Africans of the Amistad, arguing brilliantly before the U.S. Supreme Court. Now in his early seventies, he acknowledged, “More than 60 years of incessant active intercourse with the world has made political movement to me as much a necessary of life as atmospheric air. . . . And thus while a remnant of physical power is left me to write and speak, the world will retire from me before I shall retire from the world.” Adams had a stroke on the House floor on February 21, 1848, and died in the Capitol building two days later.[19]

BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR FURTHER READING:

Bemis, Samuel Flagg. John Quincy Adams and the Union. Alfred A. Knopf, 1956.

Callahan, David P. “John Quincy Adams and the Elections of 1824 and 1828.” In A Companion to John Adams and John Quincy Adams, edited by David Waldstreicher. Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

Cheathem, Mark R. The Coming of Democracy: Presidential Campaigning in the Age of Jackson. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.

Hopkins, James F. “Election of 1824.” In History of American Presidential Elections, 1789-1968, edited by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. and Fred L. Israel. Chelsea House Publishers, 1971.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kirwan, Albert D. “Congress Elects a President: Henry Clay and the Campaign of 1824.” The Kentucky Review 4, no. 2 (1983): 3-26.

Parsons, Lynn H. The Birth of Modern Politics: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and the Election of 1828. Oxford University Press, 2009.

FOOTNOTES

[1] John Quincy’s birth through his college years are covered in Adams Family Correspondence, Volumes 1-8, available online in the Adams Papers Digital Edition; the Introduction to each volume is a good starting point. Another primary source on his life and career is the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary; entries begin in November 1779 and continue for the next 68 years. For a detailed overview of John Quincy’s adolescence in Europe, see Phyllis Lee Levin, The Remarkable Education of John Quincy Adams (Palgrave MacMillan, 2015), 33-131.

[2] Adams Family Correspondence, 10:xxix-xxxiii; 12:xxvi-xxix.

[3] Adams Family Correspondence, 15:xxiv-xxv; 16:xxiii-xxvii.

[4] Adams Family Correspondence, 16:171-172.

[5] Diary and Autobiographical Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, ed. Judith S. Graham and others (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013), 1:283-284.

[6] Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy (Alfred A. Knopf, 1965), 184, 188-189, 190-191, 195, 196-220.

[7] Diary and Autobiographical Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, 2:784-785; Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy, 221-243.

[8] Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy, 317-340, 363-408.

[9] Samuel Flagg Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union (Alfred A. Knopf, 1965), 13.

[10] Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, 24-27; Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford University Press, 2007), 95.

[11] Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, 30, 47, 51.

[12] Howe, What God Hath Wrought, 247.

[13] Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, 69, 74-76; Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 251-260.

[14] The Papers of Andrew Jackson, Volume VI, 1825-1828, ed. Harold D. Moser and J. Clint Clift (University of Tennessee Press, 2002), 177-178, 187-188. Volume PDF available for download at https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_jackson/12/

[15] Diary and Autobiographical Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, 1:332.

[16] Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, 150.

[17] Diary and Autobiographical Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, 2:790-791; Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, 206-210.

[18] Bemis, John Quincy Adams and the Union, 335-351, 367-383, 416-447.

[19] Diary and Autobiographical Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, 2:793.

Close Reading Questions

Source 1. John Quincy Adams describes negativity in the campaign of 1824 in his diary, 31 August 1824

- According to this diary entry, how did Adams feel about presidential campaigning? What words stand out to you?

- Why do you think he mentions George Washington and his father, John Adams?

- How might voters have connected John Quincy Adams to the first two presidents?

Related: John Quincy Adams and his wife, Louisa Catherine Adams, both wrote about the 1824 presidential candidates in their diaries. Read what they thought about each of the men.

- How might the personalities and character of each of the candidates, as described by the Adamses, have made them favorable or unfavorable with the electorate?

- In the election of 1824, no candidate won a majority of electoral votes and so Congress voted to choose the President. Based on her letter excerpt, how might Louisa Adams have been important in John Quincy Adams winning the presidency?

Related: Read additional excerpts in which Louisa Adams discusses the role of politicians’ wives.

- Do you think Louisa Catherine Adams enjoyed being a politician’s wife? Why or why not?

- How did the election of 1824 differ from the presidential elections that had come before it?

- Why did Adams argue that it was appropriate for him to accept being named President under these unusual circumstances?

Source 4: Public perception of a ‘corrupt bargain’ leads to anger against Adams and Clay, 26 February 1825

- According to the newspaper editorial quoted, how did the public show their anger towards Henry Clay over the idea that he had formed a ‘corrupt bargain’ to get Adams into the Presidency?

- Why might they have directed their ire towards Clay instead of Adams?

Source 5: John Quincy Adams nominates Henry Clay to be Secretary of State, 5 March 1825

- Do you think the public would accused Adams and Clay of a corrupt bargain if Adams had nominated Clay to a Cabinet position other than Secretary of State? Why or why not?

- Research the men Adams nominated to each of the Cabinet positions. What do you notice?

- What were their political affiliations? Had they served in the Monroe administration? Did they appear to be qualified to fill their roles?

Source 6: John Quincy Adams Campaign Biography, A Sketch in the Life of JQA

- What was the purpose of Adams’ campaign biography?

- How did Adams want the voting public to view him?

- The “To the Public” section following the title page was added to Adams’ campaign biography in 1827. Why do you think he added this section?

Source 7: Coffin Handbill and Andrew Jackson Campaign Token, 1828

Use these Google Slides to do a close reading of the coffin handbill, with context notes for each section.

- According to this handbill, what was Jackson’s character? What made him a poor choice to be president?

- The handbill directly addresses its readers on several occasions. Who do you think the audience was for this handbill?

- What do you think the purpose of this handbill is? What did the publishers want its audience to do?

- What is the message of the Jackson campaign token? How do the token and the handbill speak to each other?

- What does this diary entry tell us about the power of an accusation, whether or not it is true?

- Do you think Adams was right in thinking that the idea of a ‘corrupt bargain’ between him and Clay harmed their political careers? Use evidence to support your thinking.

Suggested Activities (Grades 8-12)

Hook: Making Political Predictions

Materials

Activity Overview

Students will consider how the tone of political campaigns has or has not changed over time. Using a historical quote without attribution, students will make hypotheses about when it was spoken.

Analyzing Intent: Diary entries describing the 1824 presidential candidates

Materials

- Document Set: John Quincy Adams and Louisa Adams describe the 1824 presidential candidates in their diaries

- Teacher Instructions

- Student Handout

Activity Overview

Students will consider the writers’ intent behind the diary entries they wrote.

Mini DBQ: Corrupt Bargain of 1824

Materials

Activity Overview

Based on their study of the 1820s, students will analyze a set of primary sources and use them to craft a thesis paragraph on John Quincy Adams’ perception of Andrew Jackson’s accusation of a “corrupt bargain” with Henry Clay after the election of 1824.

Jigsaw: Coffin Handbill of 1828

Materials

- MHS Collections Online: An account of some of the bloody deeds of General Jackson

- Unpacking the 1828 Coffin Handbill (Google Slides)

- Teacher Instructions and Teacher Key

- Student note-taking sheet

Activity Overview

Students read and analyze background context about and quotes from each section of the “coffin handbill” to consider the purpose of and audience for this broadside. By the end, students will also be able to articulate arguments made against Andrew Jackson’s presidency and his prior military record during the campaign of 1828.

Applicable Standards

Massachusetts History/Social Science and ELA Frameworks

H/SS Skill Standards

- Organize information and data from multiple primary and secondary sources.

- Analyze the purpose and point of view of each source; distinguish opinion from fact.

- Argue or explain conclusions, using valid reasoning and evidence.

H/SS Content Standards

Grade 8, Topic 3, Standard 4

- Explain the process of elections in the legislative and executive branches and the process of nomination/confirmation of individuals in the judicial and executive branches.

Grade 8, Topic 4, Standard 6

- Evaluate information related to elections (e.g., policy positions and debates among candidates, campaign financing, campaign advertising, influence of news media and social media, and data relating to voter turnout in elections).

USI, Topic 2, Democratization and expansion

ELA Anchor Standards

Grades 6–8 Reading Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas

- Key Ideas and Details Standard 2, Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

Grades 9–10 Reading Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas

- Key Ideas and Details Standard 1, Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information and Standard 2, Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of a text.

- Craft and Structure Standard 4, Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary describing political, social, or economic aspects of history/social studies.

Grades 11–12 Reading Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas

- Integration of Knowledge and Ideas Standard 8, Evaluate an author’s premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information.

C3 Frameworks

Grades 6-8

- D2.Civ.1.6-8. Distinguish the powers and responsibilities of citizens, political parties, interest groups, and the media in a variety of governmental and nongovernmental contexts.

- D2.His.4.6-8. Analyze multiple factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras

Grades 9-12

- D2.Civ.8.9-12. Evaluate social and political systems in different contexts, times, and places, that promote civic virtues and enact democratic principles.

- D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

- D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras

Additional Resources

Additional Resources at the MHS

John Quincy Adams and the 1824 and 1828 Presidential Elections

- This secondary article links to primary sources including JQA diary excerpts, print documents, and campaign songs. It also links to additional resources.

- Learn more about the presidencies and lives of John Adams, Abigail Adams, John Quincy Adams and additional family members through primary and secondary sources!

Oath of office (manuscript written in John Quincy Adams’s handwriting), 4 March 1825

Lesson Plans at External Institutions

The primary sources in this MHS source set complement existing lessons at other institutions. Using source from the MHS source set will add John Quincy Adams’ voice to those lessons and curricula:

The American System

The American System | Emerging America

- This lesson plan looks at the emergence of the American System and frames it as the concept of Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams and John C. Calhoun (who later retracts support).

Election of 1824 and the Corrupt Bargain

Tally of the 1824 Electoral College Vote | National Archives

- This educator resource includes background content on the electoral college, a primary source document showing the tally of the 1824 Electoral College Vote, applicable standards, teaching activities and a document analysis worksheet.

Election of 1824: The Election is in the House curriculum | Edsitement

- This curriculum includes 3 lesson plans: the Denouement (context and significance of the election); the candidates and the issues; and, ‘was there a corrupt bargain?’ Aimed at high school students, this curriculum includes guiding questions, learning objectives, links to background content, activities, worksheets, links to primary sources and charts, and lesson extensions.

The Corrupt Bargain (Thematic Unit) | The Hermitage

- This unit examines “the question of whether or not our nation is a republic, or a democracy.” We recommend using excerpts from JQA’s diary from the MHS source set along with this unit.

Election of 1828

The 1828 Campaign of Andrew Jackson and the Growth of Party Politics | Edsitement

- This curriculum includes four lessons: expansion of voting base; changes in voting participation; territorial expansion and shift of power; issues in the election of 1828 and beyond (examining party politics and the positions of each party). Aimed at high school students, this curriculum includes guiding questions, learning objectives, links to background content, activities, worksheets, links to primary sources and charts, and lesson extensions.

Resource Guides for finding additional sources and information

Election of 1824

Presidential Election of 1824: A Resource Guide | Library of Congress

- This resource guide includes an introduction with the 1824 election results, primary sources, digital collections, links to external websites, and links to print resources.

1824 · Elections by Year · Presidential Campaigns: A Cartoon History, 1789-1976 | Indiana University Library

- This page has political cartoons from the Election of 1824.

Election of 1828

Presidential Election of 1828: A Resource Guide | Library of Congress

- This resource guide includes an introduction with the 1828 election results, primary sources, digital collections, links to external websites, and links to print resources.

1828 · Elections by Year · Presidential Campaigns: A Cartoon History, 1789-1976 | Indiana University Library

- This page has political cartoons from the Election of 1828.